Image courtesy of Virpi Lummaa.

In what seems a weird twist of fate, infants who are undernourished are more likely to grow up to have metabolic disorders such as cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes---conditions usually associated with obesity. But a new study casts doubt on the primary theory for why that is.

Most researchers currently believe the connection between undernourishment and metabolic disease is a case of adaptation gone wrong. A baby undernourished in the womb or in early toddler years, so the thinking goes, is being conditioned for a life of limited food. Their metabolism learns to be thrifty. When that person grows up and instead has access to ample food (and maybe even an excess of high-calorie junk food as is often the case today), their scaled-back metabolism can't take it, and the mismatch leads to disease. The rising incidence of metabolic diseases in the developing world today may be partly due to this connection. But then, what happens to undernourished kids who grow up and experience famine as an adult too? The theory predicts that, since their early years prepared them for it, those kids would have better odds during later lean years. They'd have higher survival rates and produce more offspring than their brethren. However a study of two preindustrial Finnish towns finds that the exact opposite appears to have taken place.

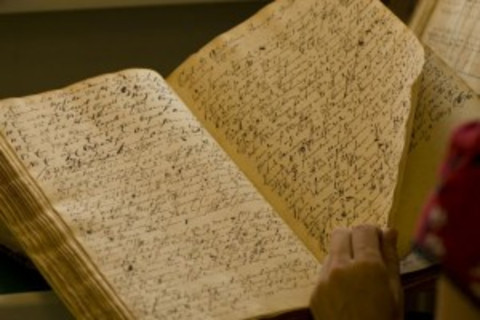

Famine Fate

Parish records used in the study. Courtesy Esko Pettay. Researchers reached that conclusion by analyzing church records detailing the birth, death, childbirth, and socioeconomic status of over 3,000 individuals from two parishes in southwest Finland. The men, women and children studied were born between 1816 and 1865, and had one thing in common---they all experienced a devastating famine from 1866-1868 in which perhaps 15 percent of the country's population died. Because these people were all of different ages, they had experienced a range of very different conditions. In the best years, crop yields of rye and barley, the two staple crops of the region, were fourfold higher than in the worst years. Thus people born in crop boom years, the researchers inferred, were better nourished as children than those born in scarce years.

A Theory in Doubt

When researchers followed these individuals through to the famine of 1866, surprisingly, those people conditioned by early scarcity coped more poorly than the rest. They were 7-10 percent less likely to survive the famine, and the women were less likely to reproduce during the famine years, the authors report

in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. That finding calls into question scientists' prevailing theory of why malnourished kids have higher rates of diabetes and heart disease. Poor nutrition in early life appears to constrain development and convey no evolutionary advantage. Scientists will therefore need to reexamine how these diseases are connected to childhood diet---which will again be added to the long list of mysteries yet to solve in the causation of metabolic diseases.