I found my new patient in bed with his eyes closed. Though in his late 70s, Dimitri had a full head of mostly dark hair and the sculpted cheeks and chin of a model.

A day earlier, he had arrived at our nursing home’s advanced dementia unit with little more than lists of diagnoses and medications. From those few pages, I learned that Dimitri had end-stage Parkinson’s, dementia and several other common chronic diseases. Like nearly half of Americans in his age group, he was taking more than five medications each day to treat his ailments — 10, to be exact. Marina, the unit’s head nurse, told me he’d been living with his wife and adult daughter, but they could no longer manage his care at home.

I said his name, but he didn’t respond. Then I touched his arm. Nothing. I shook him a bit, repeating his name in a louder voice, and finally his eyes opened. Marina, who spoke his native Russian language, explained who I was and why we were there. He stared back at us with blank, unblinking eyes.

With Marina translating, I asked Dimitri two questions: What is your name, and are you having any pain? Because Parkinson’s slows people down, we had to give him some time to respond; I sang the chorus of “Happy Birthday” in my head to make sure I waited long enough. In response to the first question, Dimitri’s lips moved, but no words emerged. He didn’t even try to answer the second one, so we skipped ahead to the physical exam.

It was remarkably unremarkable. Although one of his hands shook and his limbs showed the rigidity that’s characteristic of Parkinson’s, he otherwise seemed quite robust. He had well-formed muscles and joints, and all of his organs looked, felt or sounded as they should.

Back at the nurses’ station, I studied Dimitri’s diagnoses and medication list. His drugs were all commonly prescribed and associated with the diagnoses, although two of them — one to aid digestion and another for hallucinations, two symptoms often associated with Parkinson’s — appeared on a list of potentially inappropriate medications for older adults. Called the Beers Criteria, this list highlights drugs that have increased risks for adverse reactions. The hope is that doctors will think twice before prescribing such medicines to patients over 65 and use alternatives if possible.

I asked Marina if anyone in Dimitri’s family spoke English. She said his daughter, Svetlana, did. With Marina on standby, I phoned Svetlana.

“Oh, hello, doctor,” she said in good English. “Thank you for taking care of my father.”

I gave Marina the thumbs-up so she could return to her own work, and I asked Svetlana to tell me about her father. Dimitri had been an engineer in the Soviet Union, she said, and her mother was his second wife. They had been married 41 years and had been in the United States for eight. I asked her about Dimitri’s recent health and care, and she described a fairly typical scenario for a person with late-stage Parkinson’s. He didn’t move or speak much, was confused and incontinent, and lately spent most of his time asleep. Then I confirmed his other symptoms, diagnoses and medications, and I asked if there was anything else I should know.

“No,” she said. “I think that is everything.”

It wasn’t much, but Svetlana gave me all I needed to complete a standard medical history. From here, I focused the rest of the call on how we could help him through what I thought were the final weeks or months of his life.

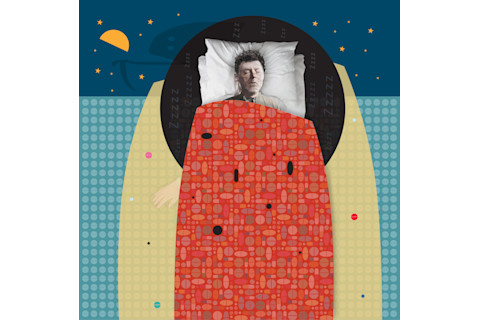

(Credit: Kellie Jaeger/Discover)

Kellie Jaeger/Discover

A Difficult Conversation

I don’t usually discuss how a patient wants to die on their first day in the nursing home. But Dimitri wasn’t eating or moving much, and I needed to know his end-of-life preferences. Svetlana appreciated the severity of her father’s situation, so I hoped that she had a sense of what treatments Dimitri would and would not want at this stage of his life. Older people almost always have more comfortable deaths when we stop drugs that are no longer helping or are meant to prevent problems they won’t live long enough to have.

As is often the case in families, regardless of background, Svetlana hadn’t talked to her father about his death. So I moved to proxy questions: Had Dimitri ever commented on the deaths of friends or family members in ways, positive or negative, that could guide us? Svetlana answered in a voice that was cooler than it had been just moments earlier. “In Russia, people die quickly. I don’t see how I can help with these questions.”

She began thanking me for my call.

“Just one more question,” I said. I wanted to get a sense of how quickly Dimitri was declining. I asked what her father had been like two weeks ago, and two months, and six months, and a year. As Svetlana reached the middle of her answer, I stood up and grabbed a pen.

Cascade of Clues

After I hung up, Marina, who missed nothing on her unit, appeared out of nowhere at my side.

“What?” she said.

“He was perfectly healthy a year ago. Mind, body, everything. Six months ago, he was still walking and talking and reading engineering journals.”

Parkinson’s is a slowly progressive chronic disease. Except for certain rare strokes, it does not reach end stage in a matter of months. A combination of drugs, though, can cause older people to suddenly show symptoms of Parkinson’s and dementia. And Dimitri’s list of meds contained possible culprits.

I called Dimitri’s neighborhood pharmacy to find out when he started taking each of his medications. Bingo! I immediately stopped eight of his medications and wrote for gradual elimination of the other two. I also asked the nurses to check him frequently over the next few days. I wanted to know sooner rather than later if I was wrong, and to make sure he remained comfortable.

By the end of the week, Dimitri could sit up. He began talking — quietly at first, but each day his voice became stronger and louder. He ate more and moved better. I ordered physical therapy. His blood pressure went up, and I started him on a medication, though a different one than he’d had before. That previous medication seemed to trigger the cascade of side effects that left him bedbound, with erroneous diagnoses of Parkinson’s and dementia.

His old blood pressure medication was a good one, effective and inexpensive, but it can cause gout. So when Dimitri’s right ankle swelled, instead of changing his hypertension drug, his doctor treated the gout flare with a strong anti-inflammatory that worsened Dimitri’s long-standing heartburn. His gastroenterologist then prescribed a medication that caused Parkinson’s-like symptoms, prompting the mistaken diagnosis. This triggered more prescriptions, and more side effects, including hallucinations and urinary problems, each of which was treated with more medications that left Dimitri sedated and confused. Every geriatrician I know has stories like this one.

Six weeks after his admission to the nursing home, Dimitri was transferred to the assisted-living unit. The first time I passed him in the downstairs hallway, I didn’t recognize him. He wasn’t even using a cane. Although he could have moved back home, it seemed he’d found a new life that suited him well. He began painting, was elected to the Residents Council and made a new lady friend. Since he was still married, this caused a small scandal, but Dimitri didn’t care. When I left the nursing home five years later, he remained healthy, active and happily coupled.

Louise Aronson is a geriatrician in San Francisco and author of Elderhood: Redefining Agin, Transforming Medicine, and Reimagining Life (Bloomsbury, June 2019). The cases described in Vital Signs are real, but names and certain details have been changed. This article originally appeared in print as "It's Not Over Yet."