A diagnosis of cancer is scary enough on its own. But cancer cells’ ability to hide out in the body after an initial round of treatment is especially insidious. And it isn’t possible yet to tell which patients still have any residual disease.

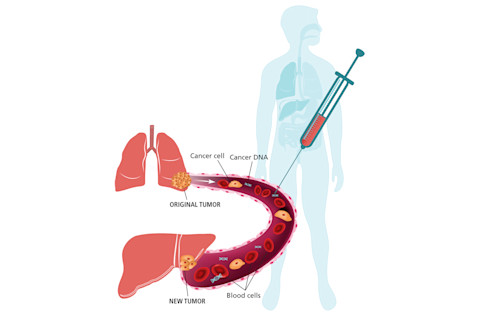

Even a few surviving cancer cells can multiply over time, moving out of the original site — the breast or colon, for example — to form a tumor in another part of the body. By the time that new tumor has grown large enough to show up on a CT scan, the cancer is likely incurable.

When cancer patients seek treatment, scars from initial therapies like radiation can make detecting new and old tumors difficult. And a traditional biopsy, a tissue sample a pathologist scrutinizes under a microscope for telltale signs of cancer, can be hard to obtain from an internal organ like the lung.

For all these reasons, doctors have high hopes for a technology still in its infancy called liquid biopsy, which looks for cancer in bodily fluids. It may identify cancer patients whose disease has persisted past the primary treatment, and help home in on effective therapies for them.

Hunting Cancer

Liquid biopsy is the result of decades of gene research, which has led to a solid understanding of cancer DNA. Doctors know now that a tumor has its own molecular pattern. “It’s like a DNA fingerprint,” says Scott Kopetz, a specialist in gastrointestinal cancer at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

Liquid biopsy can detect the distinctive DNA from cells a tumor sheds into bodily fluids, and it does so quickly. It’s also often more perceptive than a CT scan. Blood is the preferred medium for liquid biopsy for now, though eventually, other fluids like urine and saliva may come into play for some cancers. But virtually any clinic can do a blood draw, and cancer DNA reliably migrates into the blood, sometimes as fragments, which can be enough for many liquid biopsy tests to read.

Geoffrey Oxnard, an oncologist specializing in lung cancer at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, works with liquid biopsy in his practice. “We can see evidence of the cancer genome within the patient’s free-floating DNA, and we have increasingly sensitive ways of looking for low levels of that cancer DNA,” Oxnard says.

A major challenge with the technology is developing tests that are sensitive enough to detect even very low concentrations of cancer DNA floating among millions of blood cells.

“Even with a patient with stage IV cancer, the tests still can’t see the cancer 20 to 30 percent of the time,” Oxnard says. So if a liquid biopsy test comes back negative, physicians must continue to fall back on standard biopsies for their patients.

But liquid biopsy is even now pointing the way toward more tolerable treatment for some patients with advanced lung cancer. “If patients with stage IV non-small-cell lung cancer have specific alterations in [a specific] gene, they can get a highly effective oral targeted therapy with few side effects and a dramatic response,” Oxnard says. The alternative is chemotherapy, which may be less effective and have more side effects.

In a clinical setting, liquid biopsy tests designed to detect one or two genes might now cost hundreds of dollars; larger panels, with more genes, can cost several thousand dollars.

Detecting Disease

The next frontier in liquid biopsy will be putting the technology to work identifying patients who have had treatment for some types of early cancer, and who seem, based on CT scans, to be cured, but actually still have residual disease.

A different type of therapy might give those patients a second chance, says Ben Ho Park, a researcher and clinician at the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore. Because there’s no reliable way to tell who still has microscopic cancer cells in their bodies and who doesn’t, standard care now often involves simply treating almost everyone with the follow-up therapy. Researchers hope that eventually liquid biopsy tests will identify people with residual cancer, sparing those who have no signs of the disease from unnecessary treatment and leading to more effective treatment for those who need it.

Cancer can migrate into the bloodstream, as single cells or free-floating bits of DNA. In the future, liquid biopsy could offer a way to detect residual signs of cancer without invasive surgery. Information from the biopsy could also be used to create targeted treatments for individuals who need it, in addition to monitoring ongoing treatments. | Alison Mackey/Discover; Designua/Shutterstock

Liquid biopsy tests must prove their worth in clinical trials before they can be used as standard care, and those trials can take years. Park is halfway into enrolling 229 patients in a multi-institutional study of women who have “triple-negative” and “HER2-positive” cancers, two types in which he can expect at least 20 percent of patients to be cancer-free after a first round of treatment with chemotherapy.

Then, a liquid biopsy test will check for cancer. All patients in the trial will go on to surgery to remove the tissue where the tumor was originally detected. The goal is to prove that liquid biopsy can accurately flag the women who still have cancer — that the disease will then be found in those women, and only those women, during subsequent surgeries.

Kopetz, of MD Anderson, says he, too, is gearing up to enroll over 1,000 people in a study that will use liquid biopsy to look for residual cancer in patients who have had surgery for early stage colorectal cancer, but have displayed no evidence of residual disease on CT scans. He anticipates liquid biopsy will detect cancer cells in about 10 percent of patients, who will then be offered chemotherapy.

Another possible future use of liquid biopsy is monitoring ongoing treatment in advanced cancer — alerting physicians to drug resistances developing within patients and steering them away from therapies that aren’t working. Currently, oncologists might treat a tumor for two to three months, and then do another CT scan. “If you’ve guessed wrong,” says Park, “you just spent two or three months on worthless therapy.”

Park also hopes to see liquid biopsy eventually serve as a screening tool to spot early cancer in individuals who don’t have a diagnosis, but may have a high risk for developing cancer, such as women with BRCA gene mutations for breast cancer.

Increased Sensitivity

In addition to attempting to prove liquid biopsy’s worth in clinical trials like those Park and Kopetz are conducting, researchers continue to refine their tests to eliminate false negatives, as well as false positives that arise from sequencing errors or other factors.

One promising liquid biopsy test is the CAncer Personalized Profiling by deep Sequencing, or CAPP-Seq. In a 2014 study, it identified 100 percent of patients with advanced lung cancer, with few false positives. Max Diehn, a radiation oncologist specializing in thoracic cancer at Stanford University, developed CAPP-Seq with colleagues.

Diehn believes liquid biopsy’s potential extends well beyond cancer to such possible applications as detecting infections, Alzheimer’s, autoimmune diseases and the early signs of rejection of transplanted organs.

For now, liquid biopsy isn’t likely to replace tissue biopsy. “There’s still a lot of information that comes from looking at a cancer cell under the microscope,” says Kopetz.

But it does show great promise as a diagnostic and prognostic tool, and researchers are excited. “The idea of molecularly investigating a patient’s disease status through the blood, I think, will affect many other parts of medicine in the future,” Diehn says. “These tests open possibilities for new, personalized treatment strategies.”

[This article originally appeared in print as "In the Blood"]