Every flu season, vaccine makers must bet on which strain of influenza A will pose the greatest threat to the public, and millions of Americans must decide whether to get a shot. In August, virologist Gary Nabel at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) announced progress toward a universal flu vaccine; two shots of it could provide years of protection from every known influenza A virus.

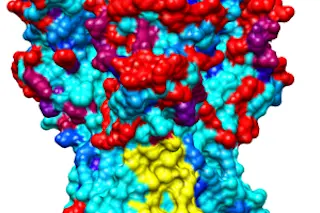

“We use a prime-boost strategy, meaning that we immunize with two vehicles that deliver the vaccine in different ways,” Nabel says. In their experimental treatment, he and his colleagues injected mice, ferrets, and monkeys with viral DNA, causing their muscle cells to produce hemagglutinin, a protein found on the surface of all flu viruses. The animals’ immune systems then began making antibodies that latch onto the protein and disable the virus. The researchers followed the DNA injection with a traditional seasonal flu shot, which ...