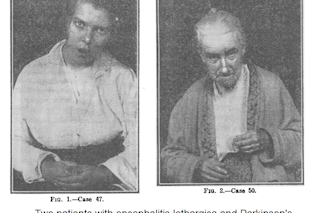

In 1917, at the height of the Great War, a new and mysterious disease emerged into the world, before vanishing a few years later. Although it was to prove less destructive than the 1918 influenza pandemic which occurred at around the same time, the new outbreak had a persistent legacy: some of the victims of the disease remained disabled decades later.

The new syndrome was first reported by Constantin von Economo, a neurologist in Vienna. He dubbed the disease ‘encephalitis lethargica’, after its most dramatic acute symptom — lethargy, or sleepiness.

Patients in the acute phase of von Economo’s disease sometimes slept all day long. Others reported that they would fall asleep as soon as they sat down in a chair. Other acute symptoms included delirium, headache, and paralysis or abnormal movements of the eye muscles. Many patients recovered from this phase, only to face a cruel twist: months or ...