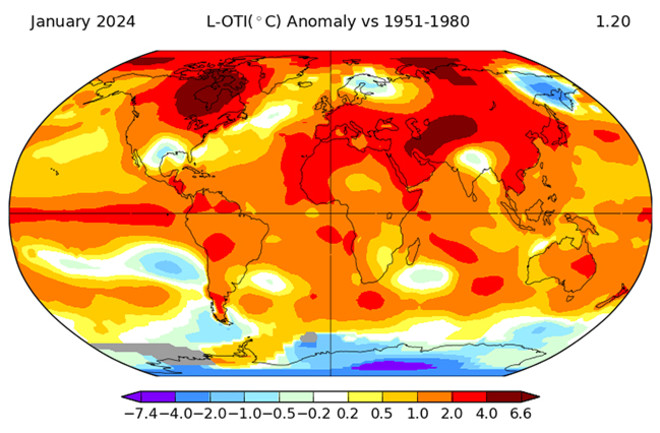

Thanks to unrelenting human-caused global warming, and with a little push from El Niño, last month continued 2023's heat streak, coming in as the warmest January on record.

Three independent analyses have come to this conclusion, the most recent released by NOAA on Feb. 14. According to the agency, January's global surface air temperature was 1.27 degrees C (2.29 degrees F) above the 20th-century average. That's very close to an assessment released by NASA a week prior.

January's unusual global warmth follows on from 2023's record-smashing temperatures. Last year turned out to be the warmest in records dating back to the 1800s. For details about what contributed to that extraordinary warmth, including the role of El Niño in nudging temperatures up, check out a two-part series I wrote on the subject here and here.

Unfortunately, another heat streak continued as well: sizzling seas. January marked the 10th straight month of record-setting sea surface temperatures.

What's more, the global average for the month was almost as high as the record-setting sea surface temperatures of August of 2023. And now, February is eclipsing August's highs, taking us further into uncharted territory.

The ongoing El Niño has played a role in this. But sea surface temperatures aren't running high just in El Niño's home turf in the equatorial Pacific. Broad swaths of ocean all around the globe also are exceedingly warm. Given that 90 percent of the warmth accumulating in the climate system is being absorbed by the oceans, this shouldn't be surprising.

Unfortunately, what goes into the oceans doesn't all stay there. "The exceptional warmth observed in the oceans is a key contributor to the record global surface air temperature for January," according to a recent analysis from the European Union's Copernicus Climate Change Service. That's also true of 2023's warmth.

Overall, recent global warming has been significant enough for the world to at least temporarily pass a significant milestone. For the 12 months ending in January, the average global temperature was 1.52 degrees C (2.74 degrees F) above the 1850 to 1900 pre-industrial average, according to the Copernicus analysis. Under the Paris Agreement, 194 nations and the European Union agreed to take actions to restrain warming to no more than 1.5 degrees C.

It must be stressed that while this is symbolically significant, it doesn't mean climatic doom is nigh. There is no magic warming number beyond which all hope is lost, or below which we're safe.

Exceeding 1.5 degrees C of warming won't suddenly trigger the collapse of the Greenland and Antarctic ice caps, or a dangerous scrambling of jet streams and ocean circulation. Those things may well happen over time if we fail to bring emissions down aggressively. But it's not as if going from 1.49 to 1.51 degrees C will guarantee any of this.

Instead, it's best to think of the 1.5 degree C threshold this way: It is a number informed by science showing that for every increment of extra warming, climate impacts will become increasingly challenging to adapt to. And informed by that science, the threshold is a political goal intended to incentivize policies for slashing greenhouse gas emissions — so impacts won't get too far out hand.

Crossing the threshold over the past 12 months also doesn't mean that the Paris Agreement is a lost cause. That's because this is all about long-term warming — meaning warming over the course of years, not months. (As defined by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, long-term is 20 to 30 years.)

As El Niño wanes, we'll likely dip back below the 1.5 degrees C threshold for a time. To keep it there will require much more aggressive action on reducing emissions of climate-warming carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases. Although many experts regard this as a long shot now, there's evidence that humanity is at long last making progress. But that will be a topic for a future column.