At first glance, the Earth’s orbit and oceans could not be more different. The former is located on the uppermost layers of the planet’s atmosphere and beyond, while the latter surrounds all the landmasses around the globe.

But there is a glaring similarity between the two: Both are vast areas with no owner, making responsible and sustainable use of them incredibly challenging.

Imogen Napper, a marine scientist at the University of Plymouth in England, says the high seas and the Earth’s orbit are both global commons. In other words, the resources are shared and accessible by all — with no single governing country or power.

As a result of this limited governance, however, they also have limited protection.

In a recent letter published in Science, Napper and her co-authors highlighted the urgency to protect the Earth’s orbit. They noted how the exploitation of what appears to be a free resource — the ocean — has led to environmental harm that no one takes accountability for.

The researchers also emphasized the need to prevent the planet’s orbit from facing the same fate: Just like plastic pollution in the ocean, orbital debris currently proliferates unchecked. And the more this debris grows, the harder it will be to clean up.

“Taking into consideration what we have learnt from the high seas,” Napper says, “we can avoid making the same mistakes and work collectively to prevent a tragedy of the commons in space.”

What Is Space Junk?

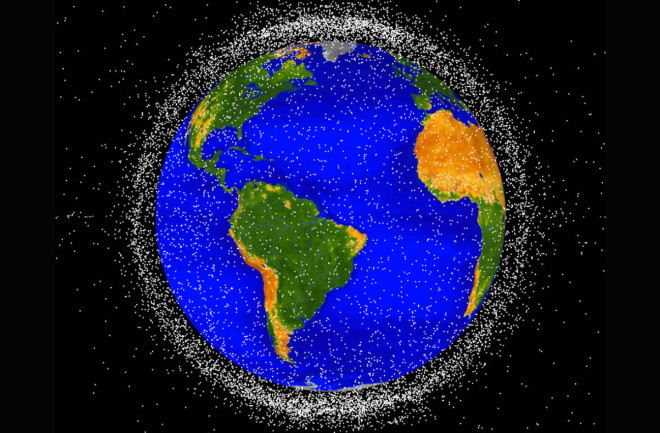

According to the European Space Agency, there are around 36,500 space debris objects greater than 10 centimeters. Another million are between 1 and 10 centimeters, and more than 130 million pieces are between a millimeter and a centimeter in size.

Most of the junk comes from the satellites and rockets that have been launched into space since the beginning of the space age in 1957, says John L. Crassidis, a professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering at the University at Buffalo.

How Much Space Debris Is There?

In fact, the total mass of all the objects in the Earth's orbit is about 12,000 tons. That’s heavier than the weight of the Eiffel Tower.

Crassidis works with federal agencies to monitor space debris, including defunct satellites, spent mission-related objects like launch adapters and lens covers, and tiny fragments from collisions. “The biggest contributor of debris is explosions in orbit, caused by leftover energy from fuel and batteries onboard satellites and rockets,” he says.

Explosions may also come from satellite interceptions by surface-launched missiles. Back in 2007, China conducted an anti-satellite test and destroyed its own Fengyun-1C weather satellite, increasing the number of trackable space objects by 25 percent.

Read More: We Now Have Satellite Traffic Jams in Space

Why Is Space Junk a Problem?

It’s important to monitor space debris because they travel very fast — at about 17,000 miles per hour — and even the smallest piece can do a lot of damage, says Crassidis.

“If two cars are traveling at 17,000 [miles per hour] in the same lane, then it’s not a problem,” he says. “But let’s say they meet at a T-bone intersection. At 17,000 miles per hour each, that will certainly be a violent collision.”

The same thing happens in space, and the risk of collision increases as more objects are put in Earth’s orbit. If one object going around the planet’s poles collides with another going around the equator, for example, the two could create thousands of new pieces of dangerous debris — increasing the probability of further collisions.

Services that rely on satellites, like weather forecasting, GPS and global telecommunications, would then be under threat. This chain reaction theory, called the Kessler Syndrome, was proposed by NASA scientist Donald J. Kessler in 1978.

Operating under a business-as-usual scenario, without putting forward debris mitigation measures, makes this scenario more likely to happen. To avoid disastrous outcomes, therefore, protecting the Earth’s orbit is paramount.

Read More: What Is Space Junk And Why Is It A Problem?

How To Clean Up Space Junk

A few startups and research programs have put forward solutions to clean up space junk.

One proposes using tether technology — a spacecraft would deploy an electrodynamic tether to latch onto space junk and then drag it down into the atmosphere. Others suggest using the satellite’s battery as a propulsion unit to generate thrust for deorbit.

However, Crassidis says none of the proposed solutions are feasible. Moving around space is different from moving on Earth, he says, and it’s not cost-feasible to build something that can only pick up a few pieces of debris.

And other approaches, like shooting a laser at small objects or using the debris to make fuel in space, are “at least 20 years away from becoming a reality,” he adds.

Read More: Space Junk Is a Problem. Is a Laser Cannon the Solution?

What Are the Existing Space Debris Guidelines?

There are already a handful of international treaties about space, including the Outer Space Treaty and the Registration Convention. But these are mostly concerned with other things: regulating space activities, for example, and prohibiting the colonization and militarization of outer space.

Back in 2010, the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA) did release space debris mitigation guidelines for missions planning, design, manufacturing and operational phases. However, says Crassidis, “we can't even get some countries to follow the simplest guideline.”

In 2021, Russia conducted a direct-ascent anti-satellite (ASAT) test to destroy one of its inactive satellites, drawing criticism from several nations for creating thousands of pieces of space debris and going against Guideline 4 — avoiding intentional destruction and other harmful activities.

The Guidelines for the Long-term Sustainability of Outer Space Activities were adopted in 2019 to provide additional guidance on the regulatory framework and safety of space activities. It seems that despite having these international guidelines, more is needed to compel governments and private companies to take responsibility for their space debris.

“An international treaty is needed, in my opinion,” Crassidis says. “It'll help slow the debris problem, hopefully enough that we can implement removal strategies before Kessler Syndrome becomes a reality.”

Read More: Don’t Count on Evolution to Save Us from Toxic Chemicals and Pollution

What Is Being Done to Prevent Space Trash?

To protect the Earth’s orbit and minimize debris, the aforementioned Science letter also called for a legally binding international treaty. Napper says it should include measures that implement producer and user responsibility for satellites and debris — and enforce collective international legislation like fines and other incentives.

An international treaty may take a while to establish; the negotiation process alone could take years. However, policymakers from individual nations could take a step toward minimizing orbital debris today by adopting their own rules and creating regulations.

In the U.S., for example, NASA requires that all satellites in low-Earth orbit must deorbit or move into a graveyard orbit less than 25 years after mission completion. And to limit the creation of space debris, the Federal Communications Commission adopted a new rule last year: It reduces the aforementioned requirement to just 5 years for U.S.-licensed satellites and those seeking U.S. market access.

“We are at an early stage, where early intervention could create real substantive change for the future,” Napper says. “Had an intervention to curb plastic pollution been initiated a decade ago, it might have halved the quantity of plastics present in the ocean today.”

Read More: Deep Ocean Pollution: The Unseen Plastic Problem