Jeffrey Sachs is used to thinking big: His area of expertise is nothing less than our entire planet. As director of the Earth Institute at Columbia University, he worries about climatic changes that could have dire consequences for us all. As director of the United Nations' Millennium Project, he works to save billions of people from disease, hunger, and the other ravages of extreme poverty. And as a leading economist and a special adviser to the Secretary General of the United Nations, he has a unique appreciation of the monetary and political obstacles to tackling these global challenges. In February, at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in St. Louis, he captivated the crowd with early results from a project in Africa that uses low-cost fertilizers and improved farming techniques to increase crop yields several times over. Sachs travels constantly, not just from country to country but from continent to continent. Discover managed to catch him between flights at his home on the Upper West Side of Manhattan.

On the spectrum from microeconomics to macroeconomics, you've gone as macro as possible. What led you in this direction?

I've been interested in one question for—my God!—about 35 years: What makes a society work well? I was lucky to be taken by my parents to the Soviet Union when I was in high school. Communism was a puzzlement. Why would there be a different kind of political system on the same planet? Which one works? Which doesn't? That was a major prod toward looking at what leads to well-being.

After the fall of Communism, you advised governments in Eastern Europe and Russia on their transition to market economies. Did things turn out the way you expected?

I don't think anybody anticipated what the health implications would be. In some parts of central and Eastern Europe, not only did life expectancy rise but heart disease went down a lot: Changes away from high cholesterol and fatty diets helped that. In Russia, on the other hand, life expectancy plummeted, and deaths of middle-aged and older men rose significantly. There is still a big debate about why. Was it alcoholism and stress from the collapse of an empire? Or were more subtle factors involved? Some nutritionists believe that there were small changes in the men's diet that were very adverse, like a low level of some micronutrients, but this is still not proved.

What about the environmental impact?

The whole Soviet system—including Eastern Europe—was incredibly energy intensive, and to a large extent, that meant coal intensive. There was a huge rise in the price of energy after the fall of Communism. So there was a very sharp decrease in fossil-fuel use, and the air improved enormously.

Are the market economies doing much better in terms of environmental sustainability?

The Soviet system was particularly miserable, but it's not as if the market system has really gotten this under control yet. We still have a major conundrum, which is that gross national product, which we take to be an indicator of material well-being in some sense, is highly correlated with energy use. Although energy efficiency is improving, so that the economy can grow maybe 1 to 1.5 percent faster than energy consumption, rising economic output and rising energy use are very powerfully connected. Economic development comes from being able to harness energy sources. Getting by without energy doesn't make sense on a basic physics level because energy is what does our work for us.

So we're not going to conserve our way out of the problem.

That's right. We can and should conserve a lot more, but it won't solve the problem. When you consider that world population will grow by another 50 percent between now and its ostensible peak around midcentury and that you have massive economic growth in today's poor countries, energy use is going to rise significantly.

Won't increasing energy use make global warming worse?

The challenge is to deploy energy sources that are safe, reliable, plentiful, and environmentally sound. Anthropogenic climate change is an extraordinarily important issue, which we have done a remarkable job of neglecting up to this point. But climate change is not caused by energy use. Climate change is caused by greenhouse gases. The question is: Are there ways to deploy energy resources without creating greenhouse gases, particularly carbon dioxide?

You recently coauthored a paper on some possible answers. What do you see as our most promising options?

Renewable or noncarbon forms of energy generation—solar power, wind, hydroelectric, nuclear—have to play a role. In addition, there is what we call carbon management, which is the big hope we have at the Earth Institute. It's proved at a very small scale and plausible, although unproved, at a much larger scale. Basically, you use fossil fuels in an environmentally sound way by making sure that carbon dioxide is not emitted into the atmosphere but instead collected and put safely underground. What's unknown is whether that can be done on a global basis. Roughly 25 billion tons of carbon dioxide are produced each year, and that's a lot of storage.

How can we find out if carbon management will scale up?

We should sit down with our counterparts in India, China, Brazil, Russia, and the European Union and build a number of thermal power plants with carbon management, so we learn how this technology works. What are the costs? What are the risks? What are the regulatory problems? What is the geologic storage capacity? Where should power plants be located if we're going to go this way?

Why aren't we doing that already?

Although the Bush administration says that technology offers the biggest promise of a way out of our environmental problems, the lassitude of the administration is shocking and shameful, because there is a complete disconnect between the importance of the issue and the casualness with which it's treated—not to mention deliberate obfuscation as well. The president is deliberately running from this issue, so there's no leadership whatsoever.

It's not just the president, of course. Much of the American public is still skeptical about climate change too.

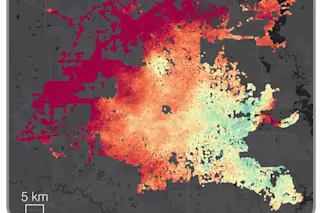

The public needs to understand that we are contributing to grave danger worldwide. Climate change is not just an issue for the future. We're in the middle of it right now. That signal is translating into all sorts of events—droughts, intense rainfall, more intense tropical cyclone activity, crop stress, heat waves, and so on.

But it's not easy to demonstrate cause and effect—for instance, that a particular storm is the result of global warming.

It is absolutely true that climate scientists are extremely cautious about attributing any event to anthropogenic climate change, but an increasing number of such attributions are being made with high confidence in the scientific literature now. One breakthrough paper was about the European heat wave of 2003, where modeling showed that under the hypothesis of unchanged climate, the frequency of such a heat wave occurring was something like once in 5,000 years. The conclusion of the authors was: If this would normally happen only once in every 5,000 years, yet this event is consistent with the model of anthropogenic climate change, then there's really a good, logical reason to attribute this heat wave to man-made change.

At the same time, many people both here and abroad worry that addressing global warming will kill the economy.

We have a lot of screaming that, in my best guess, is really powered by vested interests. There is a lot of fear. But what Klaus Lackner and I showed in the paper we published last year is that the cost of deflecting our trajectory away from a doubling of carbon emissions, using optimistic but plausible technological projections, looks to be significantly below 1 percent of gross world product. If carbon emissions doubled, the risks to millions of species, to ecosystems, to farming, to sea levels, and to all the rest would be huge. Now, if the world were told this clearly and asked, "Should we head this off at a cost of between 0.1 percent and 0.3 percent of gross world product?" the answer would, in my opinion, be overwhelmingly yes.

In your role as director of the U.N.'s Millennium Project, a lot of your work concerns Africa. Why have so many countries in Asia been able to develop while Africa has not?

Poorer countries have benefited from the diffusion of technologies developed elsewhere. Certain kinds of technology, like cell phones or the Internet, can work essentially anywhere. But when you think about health, agriculture, or construction, there is an ecologically specific challenge. In the case of Africa, conditions are tougher, and diffusion has been weaker. Take malaria. Malaria is an absolutely devastating disease for Africa. Africa's ecology is uniquely suited to malaria transmission. But it's a disease that Americans hardly care about. Our biggest research on malaria has come when American soldiers have been fighting in tropical countries, like the Pacific Islands in World War II or in Vietnam. When we're not in the middle of a tropical war, malaria concerns in this country disappear. So there's Africa, which has holoendemic malaria—it's everywhere—and it's an incredible burden on the society and on the economy, but almost no work gets done on it. This has been recognized for years but not particularly acted upon until the Gates Foundation came along and restarted or energized a lot of research for diseases of the poor. Agriculture is another area where Africa has it tougher.

You've noted that the green revolution passed Africa by. Why?

The green revolution in the 1960s was a package of technologies that included high-yield variety seeds combined with fertilizer and small-scale water management. That package was the critical step out of extreme poverty for Asia. But it did not apply in Africa. The first high-yield seed varieties were wheat, which is a temperate-zone crop, and paddy rice, which is an irrigation-based technology. Wheat and rice being improved was good for India and China, but it was largely irrelevant for the staple cassava or maize crops in Africa. Now, by the 1980s African high-yield seed varieties were becoming available. But at that point you had a technology that was too expensive for impoverished farmers to use, and the philosophy of the United States and the World Bank was, "If they can't buy it, it must not be useful to them." The vast majority of African farmers are still planting low-yield seeds without even the benefit of fertilizer, and the harvests that they're getting are a third or a fourth or a fifth of what they ought to be getting, and the result is mass hunger.

How are the Millennium Project and the U.N. helping?

We are operating a partnership with villages across Africa called Millennium Villages. We're testing easily deployed technologies: bed nets to combat malaria, high-yield seeds, fertilizer. We hypothesize that at a low cost one can have an enormous effect on the quality of life. We're in the second year of a five-year project, and the results are astounding. Each harvest that we've had, first in Kenya, then in Ethiopia, and recently in Malawi and in Rwanda, has tripled or quadrupled the amount of food produced. We believe the villages will earn enough income so that after five years they'll be able to take on the expense of these technologies. The idea is not only to show that you can grow more food but that you can make an economic transformation that's self-sustaining. We see increased food production as the entry point into the breakout from extreme poverty. This is, in essence, how India's escape from extreme poverty got started.

What else is the Millennium Project doing?

World leaders have agreed on goals for the project: to fight poverty, hunger, disease, and the deprivation of basic needs like safe drinking water and sanitation. Such goals are often adopted with the tacit understanding that they are good for a speech or a headline, but the view is, "Oh, don't take them seriously, they're just words." My assignment is to take them seriously and remind the world not only that we've agreed to do these things but that they are achievable and vitally important. I am trying to mobilize scientists, technologists, the corporate sector, and civil society all to say that practical things can be done that will make a difference in the fight against suffering and instability. Last year, all the European donor countries committed to spend 0.7 percent of their GNP in foreign aid. If they actually honor those commitments, that's a phenomenal breakthrough.

The United States didn't join that commitment, even though Americans are, in my experience, very generous people. Why?

One reason is that we're diverted constantly by war. Yet there is overwhelming evidence to show that the probability of a country falling into conflict, either civil war or cross border, is higher the poorer the country is. The CIA, which established something called the Political Instability Task Force years ago, has found this repeatedly. It's actually part of our national security doctrine—the economic development of poor regions is part of U.S. national security. President Bush has made statements not different from mine. He just doesn't advocate the funding that could make this work. From my own experience—I've worked with well over 100 governments around the world—positive inducements are extremely powerful. Negative inducements, like military force, generate resistance, nationalism, and fear, which easily spiral out of control. Whenever we've invested in development, whether it was European reconstruction, Korea and Taiwan in the 1950s, or the green revolution, the long-term benefits have been huge. Whenever we have let places collapse under the weight of extreme poverty, whether Afghanistan or the West Bank, we've ended up paying horrendous consequences.

It sounds as if you're trying to establish a new kind of international ethics, rooted in science and economics.

When I discuss morality, it's not about natural law. I view morality in a very instrumental way: Can we live together without killing each other? We need principles that address the difficulty of surviving and prospering on a crowded planet. We are not tribal bands off on our own in our own part of the forest. We're absolutely on top of each other, and that requires a kind of practical ethics we don't have yet.

What do you think the world will be like 50 years from now?

I believe there is a clear path to shared prosperity through knowledge and science. I also believe there is a very real possibility of an environmental, health, or military catastrophe. Fundamentally, this is about choice. The future is not a roulette wheel that we sit back and watch as worried spectators. It's a matter of work. We should see the risks, see the positive possibilities, and do what we can to make sure that future outcomes are the ones that we desire.