Of all the evidence scientists have collected about our planet's health, none is more important than a long-running climate record gathered at a lonely outpost atop Hawaii's Mauna Loa volcano.

The record, gathered for more than 60 years at the storied Mauna Loa Observatory, has played a critical role in our understanding of climate change by charting the inexorable rise of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. But now, lava flowing from the erupting volcano, has cut access and power to the site, halting this critical monitoring of climatic health.

"It's an incredibly detailed, informative record dating back to the 1950s," says Ralph Keeling, Director of the CO2 Program of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography. "So if you want to know how the cycling of carbon and our earth system have changed between then and today, you need that record."

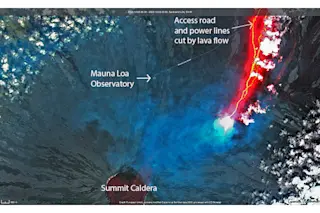

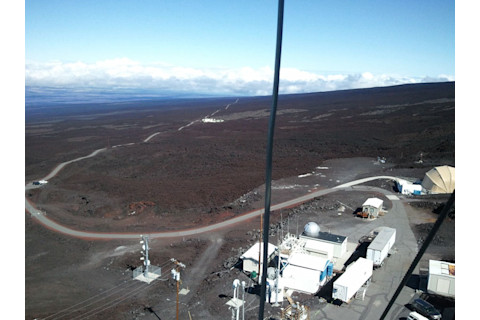

This image, taken midday during a helicopter overflight of Mauna Loa's eruption on December 5, 2022, shows a lava flow cutting across the road that provided access to the Mauna Loa Observatory. The MLO is the world's foremost monitoring site for carbon dioxide and other climate-altering greenhouse gases. After a lava flow cut the access road and power lines to the site, CO2 monitoring was put on hold. (Credit: USGS)

USGS

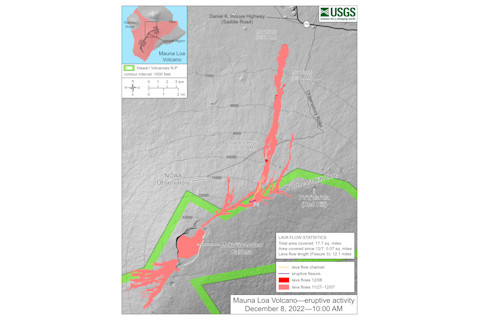

Since the eruption of Mauna Loa in Hawai'i began on Nov. 27, 2022, lava has flowed as much as 12.1 miles (as of Dec. 8) from the volcano's Northeast Rift Zone. Flows have crossed the access road and cut the power line to the Mauna Loa Observatory, knocking it out of action. (Credit: USGS)

USGS

With the Mauna Loa Observatory, or MLO, out of action, possibly for many weeks, experts say significant impacts to our understanding of the climate system are possible. "It's a serious blow, that's for sure," says Keeling, who oversees one of two greenhouse gas monitoring programs at the observatory.

Given the stakes, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which runs the observatory, is working on ways to restore monitoring even before the lava stops flowing, according to Keeling. (As of Dec. 8, the supply of lava had slowed, but not stopped, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.) Another possibility NOAA is working on is to find a way to obtain atmospheric CO2 samples at a suitable alternative site until the MLO can be brought back online.

These efforts are only in their early stages. And there is already a growing gap in the CO2 record. Moreover, whatever interim solution may be devised, "it won’t be the full scope of what has been done at the station," Keeling says. "So there will be long term impacts."

A lava fountain erupting from a fissure on Mauna Loa, as seen during a fly-over on December 8, 2022. U.S. Geological Survey scientists described the fountain as "jet like." (Credit: USGS image by T. Orr.)

USGS image by T. Orr.

Pieter Tans, a former senior scientist with NOAA's Global Monitoring Laboratory, now retired, notes there is no other CO2 monitoring site with the same advantages as Mauna Loa. "There are many other places where observations are being made, but MLO is the world's foremost observatory for greenhouse gases," he says. (Note: as a retired NOAA scientist, the views expressed here by Tans are his own and do not necessarily reflect those of the agency.)

Why Operations at the MLO Are So Critical

The observatory's location in the middle of the Pacific at an elevation of 11,135 feet above sea leve l isolates it from local and regional CO2 sources — factories or highly urbanized areas, for example — and allows for sampling of air that is very well mixed. (Keeling notes that CO2 emissions from the Mauna Loa volcano itself pose no significant problem because they are relatively small, and sampling operations can be flexibly scheduled to avoid times when the wind is blowing in the wrong direction.)

All of this makes for a relatively unadulterated, overall picture of what's happening with CO2 in the temperate latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere, Tans says.

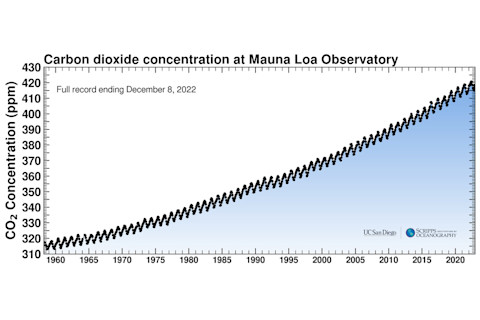

Named the "Keeling curve," after Charles David Keeling, Ralph's father, who began the effort in 1958, it's also the longest-running such record that we have.

The iconic Keeling Curve plots the inexorable rise of climate-altering carbon dioxide in the atmosphere since the 1950s. (Credit: Scripps CO2 Program)

Scripps CO2 Program

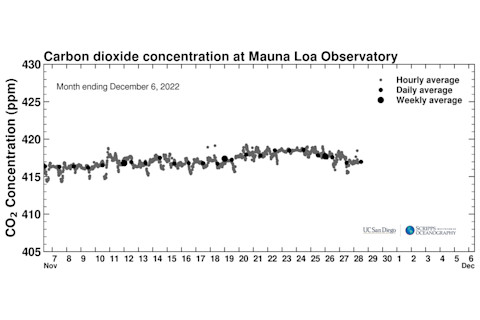

On Nov. 29, 2022, the long-running record of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere collected atop Mauna Loa in Hawai'i was abruptly interrupted when lava flows cut power to the monitoring station. (Note that the actual data seen here, prior to the cut-off, is preliminary and may be updated. Credit: Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego)

Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego

"The Mauna Loa record, and a similar one collected at the South Pole, really probe big parts of the atmosphere," Ralph Keeling says. "It's a bit like taking an important measure of human health like blood pressure. The CO2 records are wholistic measures of planetary health."

With human health, "everything might look fine on the outside, but in reality you could have high blood pressure," Keeling says. And that would be a threat to your well-being over the long run.

With planetary health, everything actually did look relatively fine on the outside, at least for awhile. But like a person prone to hypertension who eats too much sodium, we humans were pumping large amounts of CO2 into the circulatory system of Earth's climate. For years, monitoring atop Mauna Loa was showing the result: CO2 in the atmosphere was rising year by year, and decade by decade, threatening the planet's well being.

Much as hypertension can silently creep up on someone for years, ultimately leading to a heart attack, that CO2 was silently creeping up on the planet as a whole, until the impacts — increasing temperatures, melting ice caps, rising sea level, worsening extreme events like heat waves, droughts, wildfires, and deluges — became undeniable.

Had we payed earlier and more serious attention to the Keeling Curve's measure of planetary health, perhaps we could have avoided some of these impacts.

The MLO's CO2 monitoring facilities, which are operated by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, sit isolated on the flanks of Mauna Loa, with a lonely access road stretching off into the distance. The access road and power lines to the facility have been cut by lava flows from an eruption that began on Nov. 27, 2022. (Credit: Scripps Institution of Oceanography)

Scripps Institution of Oceanography

It is still critically important to keep monitoring the health of our planet's life support systems — even more so now than ever before. Which is why the growing gap in the Mauna Loa record is so concerning.

Irreplaceable Gap

That ever widening gap can never be recovered, Pieter Tans observes. And this could affect climate and carbon cycle science in significant ways.

We often tend to think of CO2 and climate as a one-way street: Humans pump CO2 into the atmosphere, and that causes climate change. But it's actually a two-way street: Plants and soils can help offset humankind's relentless emissions of CO2 by absorbing the gas from the atmosphere.

We can use this as part of a multifaceted strategy to mitigate climate change. But stresses from climate change can undermine the ability of plants and soils to provide this valuable service. So if we want to know how much we can depend on them going forward, scientists need detailed information about the flow of carbon between the biosphere and the atmosphere, and how it is shifting due to climate change.

For scientists to see how this complex process plays out when anomalous climatic events like severe, widespread droughts occur, they need an accurate, continuous record of what's happening broadly in the atmosphere. With monitoring at Mauna Loa paused, it will be more challenging for scientists to discern how CO2 affects these events, and visa versa.

As Tans puts it, the gap in the Mauna Loa record "could increase the uncertainty of relationships that we can trace between CO2 and drought, precipitation, and other climate anomalies on a seasonal and annual scale."

Even more specifically, Tans notes that scientists can examine how climate anomalies such as a severe drought affect the exchange of CO2 between plants and the atmosphere across a very small area — on the order of a kilometer across. Working at such a small scale makes it easier to see what's going on, in detail. But by definition, these data are very local. By themselves, they can't tell you what's happening at a broader scale.

To get to that broader scale, scientists can analyze data from multiple sites and combine that with modeling to make predictions about how drought affects CO2 in the atmosphere, and visa versa. "But when all is said and done, what we measure at MLO has the very last word on the sum of all those predictions," Tans says.

In other words, MLO's sampling of CO2 represents a good average of what's happening across the temperate and boreal latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere. And that's essential for scientists trying to get the final word on the give and take of CO2 between the atmosphere and plants and soils that are being hammered by climate impacts.

Thus, the stakes in getting the MLO observatory back online are pretty high. Full operations probably won't be possible until lava stops flowing across the access road and power lines. And even then, crews will have to wait until the lava cools down, which could take weeks.

Looking to the past can provide some ideas about how things might play out this time. The previous eruption, which occurred in 1984 and also paused MLO's operations, lasted about three weeks. But in that case, the access road was unaffected, according to Keeling. That made things less challenging.

The Mauna Loa eruption of 1855 began in a similar location and sent lava flows in roughly the same direction. That one lasted for six months.

The prospect of a similarly long pause in operations makes efforts to establish interim solutions all the more critical.

For now, seismic activity is continuing beneath the currently active fissure, according to the U.S. Geologic Survey. The ground continues to rumble because magma is still rising up into it. When it will stop is anyone's guess.

Note: An earlier version of this story misidentified Pieter Tans as well as NOAA's Global Monitoring Laboratory. I have corrected those errors in the text.