Sacrificing a small patch of your garden may be enough to greatly improve the plight of bees at a time when pollinators are suffering huge declines. “A small wildflower patch or a mini meadow in your garden could have big benefits for biodiversity,” says Janine Griffiths-Lee, a PhD candidate in conservation biology at the University of Sussex. “Just a little corner would do wonders.”

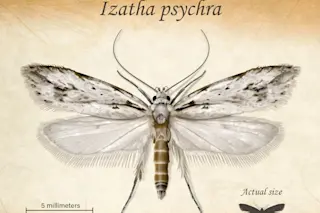

Pollinators are declining around the world for a number of reasons, including pesticide use, climate change and predation by invasive species. And it’s not just pollinators — insects in general are dropping hugely in abundance and diversity across the planet, ripping out a whole baseline ecosystem that provides food for the next level up on the food chain.

Without pollination, many of our crops and orchards couldn’t produce the fruits, nuts and grains that feed not only us, but much of the livestock that we also ...