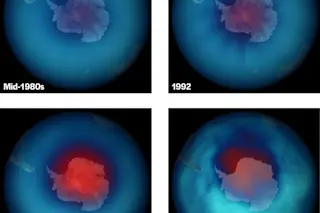

Good news for fans of planet Earth: The seasonal hole in the ozone layer over Antarctica was at its second-smallest point in the past 20 years, according to new research from NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Could this be the first real sign that the ozone layer is recovering after decades of destruction?

The ozone layer, which includes oxygen and nitrogen as well as ozone, forms a protective belt in the stratosphere about 10 to 18 miles above the Earth, reflecting the sun’s harmful ultraviolet radiation. In the 1960s and ’70s, the widespread release of chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), chemicals used primarily in spray aerosols, led to a partial breakdown of the layer.

Since the 1980s, the ozone layer above Antarctica has been especially affected because the region’s frigid temperatures speed up the conversion of CFCs to chlorine, which also accelerates ozone breakdown. Sunshine in the southern spring and summer creates even more ozone-depleting gases, leading to the massive destruction of up to 65 percent of the ozone layer.

While the reduced depletion was due mostly to higher temperatures on the icy continent, scientists are hopeful that the chemical levels have dropped enough that the result is a shrinkage of the ozone hole each season. “If these trends continue for the next few years,” says atmospheric scientist Bryan Johnson of NOAA in Boulder, Colo., “we’ll have confidence things are improving.”