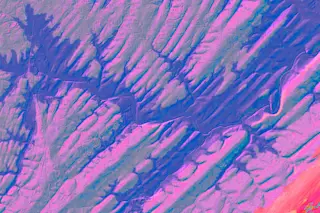

Ribbons of blue — the modern Raritan and Neshanic rivers — slice across a landscape that’s key to understanding Earth’s deep-time climate cycles. This colorized elevation map captures a 40-square-mile chunk of an ancient lakebed in central New Jersey. The purple and gray stripes represent layers of sediment that were deposited horizontally in a huge lake, then tilted and beveled off by erosion so the layers could be seen in cross section from above.

Looking down on the cross section, you can see ridges (purple) made of hard, compressed sediment deposited during wet periods. Erosion has eaten away at softer sediments (gray) originally deposited in dry periods.

By studying the layers here and at a similar site in Arizona, Columbia University geologist and paleontologist Paul Olsen and his team identified a 405,000-year cycle between wet and dry climates on Earth that has remained unchanged for more than roughly 200 million years.

This cycle appears to be due to shifts and wobbles in the orbit and tilt of Earth, caused by the gravitational pull of other planets. Usually, researchers employ mathematical models to sort out these complex factors. However, because each individual factor also changes over time, models are only reliable going back about 60 million years.

The 405,000-year-long cycle Olsen’s team identified is literally carved in rock, so it’s a yardstick against which the math-based models’ more changeable climate influencers can be measured. The revelation allows scientists to confidently reconstruct Earth’s climate cycles going back almost three times as far as before, to about 200 million years.

[This article originally appeared in print as "What Lies Beneath."]