This article appeared in the March/April 2021 issue of Discover magazine as "Tiny Trash Factories." For more stories like this, become a subscriber.

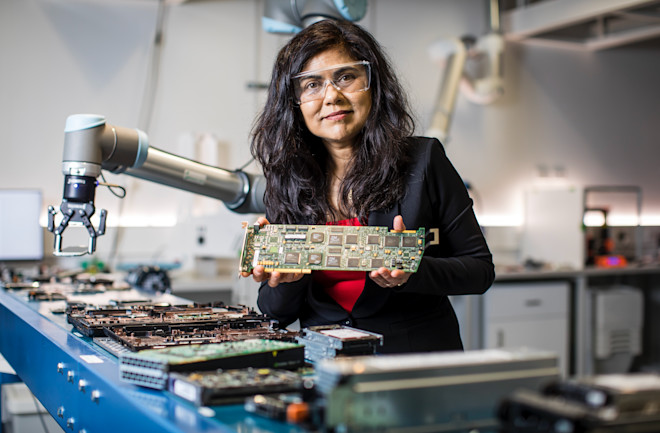

Not all waste has to go to waste. Most of the world’s 2.22 billion tons of annual trash ends up in landfills or open dumps. Veena Sahajwalla, a materials scientist and engineer at the University of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia, has created a solution to our massive trash problem: waste microfactories. These little trash processors — some as small as 500 square feet — house a series of machines that recycle waste and transform it into new materials with thermal technology. The new all-in-one approach could leave our current recycling processes in the dust.

Sahajwalla launched the world’s first waste microfactory targeting electronic waste, or e-waste, in 2018 in Sydney. A second one began recycling plastics in 2019. Now, her lab group is working with university and industry partners to commercialize their patented Microfactorie technology. She says the small scale of the machines will make it easier for them to one day operate on renewable energy, unlike most large manufacturing plants. The approach will also allow cities to recycle waste into new products on location, avoiding the long, often international, high-emission treks between recycling processors and manufacturing plants. With a microfactory, gone are the days of needing separate facilities to collect and store materials, extract elements and produce new products.

Traditionally, recycling plants break down materials for reuse in similar products — like melting down plastic to make more plastic things. Her invention evolves this idea by taking materials from an old product and creating something different. “The kids don’t look like the parents,” she says.

For example, the microfactories can break down old smartphones and computer monitors and extract silica (from the glass) and carbon (from the plastic casing), and then combine them into silicon carbide nanowires. This generates a common ceramic material with many industrial uses. Sahajwalla refers to this process as “the fourth R,” adding “re-form” to the common phrase “reduce, reuse, recycle.”

In 2019, just 17.4 percent of e-waste was recycled, so the ability to re-form offers a crucial new development in the challenge recycling complex electronic devices. “[We] can do so much more with materials,” says Sahajwalla.

“Traditional recycling has not worked for every recycling challenge.” She and her team are already working to install the next waste microfactory in the Australian town of Cootamundra by early 2021, with the goal of expanding around the country over the next few years.