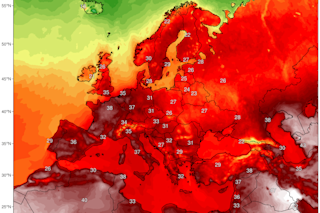

Here we go again, another Western European heat wave.

Except this one is even more intense than the one back in June and early July — an event that research tentatively suggests was made at least five times more likely to occur by human-caused climate change.

Now, with another “heat dome” strengthening over the continent, high temperature records have tumbled once again. In fact, Germany may have just seen the highest temperature ever recorded in the country: 104.9 degrees F.

Even more brutal heat is on the way. The forecast for Paris for Thursday, July 25th is for a high temperature of 105 F. If the mercury climbs that high, it would break the previous record of 104.7 F set more than 70 years ago.

I’ll get into the connections between climate change and heat waves in a just a bit. But first, the proximate cause of this one is a big, intense area of high pressure — that heat dome — with the jet stream flowing around it in a pattern called an “omega block.”

Here’s what the Greek letter omega looks like:

(Credit: Wiktionary)

Wiktionary

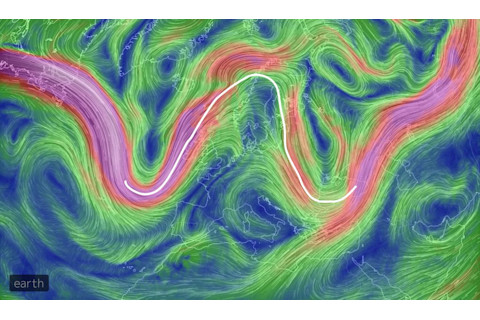

And here’s what the flow of the jet stream looked like over Europe on July 23, 2019:

A big wave in the jet stream took on the shape of the Greek letter “omega” — Ω — over a large portion of Western Europe on July 23, 2019 as a heat wave was building. The pattern is associated with an area of high pressure and a surge of hot air from as far south as North Africa. (Source: Earth Simulator, earth.nullschool.net)

Bends in the path of the jet stream naturally take on a wave-like pattern like this. The upward crests and downward troughs form what’s known as “Rossby waves.”

So now, instead of thinking of the Greek letter omega, imagine the cross section of a wave in the ocean.

These natural waves bring warm air from the south under the wave crest, and cool air from the north down into the troughs on either side of the crest. Progressing from west to east, the Rossby waves that trace out the path of the jet stream are associated with naturally changing weather conditions.

But sometimes the upward-arching wave crest is particularly tall — as it is in this case. And its progression from west to east can slow down, or even stall. The result: particularly intense and persistent heat waves.

Research by Michael Mann, a climate scientist at Penn State University, and European colleagues shows that human-caused climate change is influencing these patterns. As he wrote in a March 2019 piece for Scientific American:

My collaborators and I have recently shown that these highly curved, stalled wave patterns have become more common because of global warming, boosting extreme weather.

The details are pretty complex — and Mann does an excellent job of explaining them in his Scientific American story. But here’s the long and short of it:

As the world warms under the influence of the carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases we’re emitting into the atmosphere, the Arctic is warming faster than any other area on Earth. The phenomenon is known as Arctic amplification, and it is related to the decreasing extent of the Arctic’s floating lid of sea ice. (I wrote about it in detail in this story for bioGraphic magazine.)

The amplified warming in the Arctic has reduced the difference in temperature between the high north and areas to the south. That’s important because it is this temperature difference that helps drive the jet stream.

When the temperature difference is particularly high, jet stream winds tend to blow more forcefully. The result: The flow of the jet stream is straighter, resulting in Rossby waves with less pronounced crests and troughs.

In summer, the difference in temperature between the Arctic and latitudes directly to the south is less than it is in winter. That saps the strength of jet stream winds, resulting in Rossby waves with somewhat bigger crests and troughs. It also slows their progression from west to east. All that is quite natural.

But now here’s the key part: Add increasing Arctic warmth to the equation, and the effect can become even more pronounced. The movement of Rossby waves can stall completely, creating huge standing Rossby waves in the atmosphere.

And there’s even more: Research shows that human-caused warming is causing the atmosphere to act as a kind of waveguide.

You can think of the waveguide as a kind of corridor in which the Rossby waves become trapped. When this happens, the standing waves resonate and grow still more. The scientific term for this phenomenon is “quasi-resonant amplification,” or “QRA.”

Thanks to QRA, really big wave crests associated with intense high pressure and heat can build — not unlike the one over Europe right now. And because these are standing waves, they remain over the same place for awhile, locking in the heat.

Is this what we’re seeing right now in Europe? I posed that question to Michael Mann in an email. He responded that the first of this year’s European heat waves has been linked by his colleagues to this QRA phenomenon. “We can say that this mechanism was certainly implicated in that case,” he says.

But he added that he does not think “the numbers have yet been crunched for the heat wave that is currently playing out.” So it is just too soon to say for sure.

“What I can tell you is that many of the most persistent summer weather extremes reported over the last two decades, including the 2003 European heat wave, the 2011 Oklahoma and Texas heat wave/drought, the 2010 Russian wildfires and Pakistan floods, 2016 Alberta wildfires, and just about all of the extremes of summer 2018, were associated with QRA.”

As I said, this is all pretty complex. So let me try to summarize:

Human-caused global warming has set up self-reinforcing chains of events, starting with…

the Arctic warming more than lower latitudes, leading to…

more sluggish jet stream winds, which…

results in the Rossby waves that they trace out becoming more pronounced and persistent.

The warming also makes it more conducive for atmospheric waveguides to set up. Thanks this phenomenon, known as quasi-stationary resonance, or QRA…

the Rossby waves get bigger and more persistent still, causing…

hotter, longer-lasting conditions under the wave crests.

Whew!

There’s also a simpler, more straightforward way that human-caused global warming is making heat waves more intense: When the heat starts to build, it happens on top of a baseline that’s already warmer.

In fact, according to the European Environment Agency:

The average annual temperature for the European land area for the last decade (2009–2018) was between 1.6 °C and 1.7 °C above the pre-industrial level, which makes it the warmest decade on record.

Add a heat wave on top of that, and the consequences can be brutal. More than a dozen deaths were attributed to Europe’s June heat wave.

And research suggests that the 2003 European heat wave — which began in June and lasted into August — could have contributed to the deaths of 70,000 people across the continent.