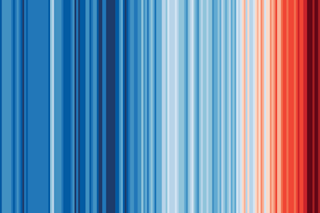

Photograph by Timothy Archibald. Earth's rising temperatures are starting to affect plants and animals around the planet. Territories have moved, breeding seasons have shifted, and some organisms may already have gone extinct. Ken Caldeira of Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California takes the long view in understanding how to respond. Using computer models, he simulates Earth's climate into the distant past and far future. He also uses modeling to evaluate techniques that might stem the rising thermometer. Caldeira spoke with Discover associate editor Kathy A. Svitil.

What are the consequences of rising carbon dioxide levels? Researchers say Earth might warm two to five degrees Celsius [roughly three to nine degrees Fahrenheit] over the next century. A two-degree increase is like moving the climate bands 250 miles poleward in 100 years, or around 30 feet each day. Squirrels might be able to move at those kinds of rates, but an oak ...