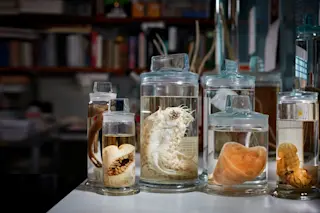

When Larry Madin first became aware of parasites in the open ocean, he was a graduate student living in a sort of scientists’ commune in the Bahamas. It was a large, unfinished house on Bimini, with plywood floors and bare holes for windows and one bathroom for the one or two dozen biologists, spouses, and children who lived there. It was an interesting experience, says Madin. Fortunately we were all young. The expedition had been organized by Madin’s adviser at the University of California at Davis, an ornithologist turned marine biologist named Bill Hamner. Hamner got his students to live on fish and rice and in close quarters for a year with the understanding that they were doing something new--scientifically new. From Bimini they could take a small boat just half a mile offshore and scuba dive in the Gulf Stream every day. They could watch the gelatinous animals that ...

At Home With the Jellies

The best plan in the open sea is to be gelatinous. Failing that, you should grab onto something that is.

More on Discover

Stay Curious

SubscribeTo The Magazine

Save up to 40% off the cover price when you subscribe to Discover magazine.

Subscribe