Conspiracy theories are something of a plague for scientists: no matter how much research is done on some topics, a vocal minority will insist that the facts just aren’t true.

So it’s gone for vaccines, climate change and 9/11, and so it will go on, in all likelihood. In some cases, it may be best to simply ignore the conspiracy agitators, but, as a 2010 article in EMBO Reports points out, some of the biggest scandals start out looking very much like outlandish conspiracy theories — the Watergate scandal in the 1970s, for example.

Perhaps the best attitude toward conspiracies is to follow the advice popularized by Carl Sagan: “Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.”

When taking on some of the more outlandish theories out there, scientists must weigh the the public benefit of lending knowledgeable analysis to questionable hypotheses with the chance they’ll provide a semblance of legitimacy to the claim they’re studying. In the end, a scientific paper may not win over hardened conspiracy theorists, but it may at least quell the suspicions of those caught in the middle.

As one survey paper looking at the viability of the “Chemtrails” conspiracy puts it: “Our goal is not to sway those already convinced that there is a secret, large-scale spraying program — who often reject counter-evidence as further proof of their theories — but rather to establish a source of objective science that can inform public discourse.”

Here, we take a look at five conspiracy theories that scientists felt compelled to weigh in on, from nutrient-draining microwaves to shaggy mountain-dwelling hominids.

Chemtrails

(Credit: Gajus/Shutterstock)

Gajus/Shutterstock

As the world has become more developed and air travel even more of a necessity, the number of passengers on airplanes has climbed steadily, and proof is in those streaky clouds in the sky.

For some, those vapor trails that mark a plane’s passing hint at something more insidious: a secret government program spreading harmful chemicals across the country. The white clouds wouldn’t form naturally, according to chemtrail theorists, and there must be some sort of mysterious ingredient involved.

Researchers at the University of California-Irvine and Stanford published a comprehensive survey of 77 scientists who had published papers related to atmospheric deposition and contrails. All but one said that they had never encountered evidence of a secret government program intent on spreading chemicals via jet planes, and every scientist surveyed said that the suspicious vapor trails could be easily explained by the natural interactions of jet exhaust and the atmosphere.

Fluoride

(Credit: Tamas Panczel-Eross/Shutterstock)

Tamas Panczel-Eross/Shutterstock

While the government may not be injecting chemicals into our air, it is putting chemicals into our water.

Fluoride has been added to the drinking water in the U.S. for decades to reduce cavities, and a 2013 study in the Journal of Dental Research indicated it works. While the element is naturally present in most water at low levels, as well as in some foods, the additional fluoride gives our teeth an additional level of defense against bacteria.

During the 1950s, aided in part by fears of a Communist insurgency, fluoride’s pervasive presence in homes across the country led some people to claim that it was in fact being used as a mind-control drug. As the thinking went, secret forces were feeding us chemicals designed to erode our willpower under the guise of promoting dental hygiene.

Fluoride can actually be quite harmful to us, but only when consumed at concentrations far greater than those found in tap water. According to the World Health Organization, concentrations of fluoride are usually kept to around 1 part per million. To see detrimental effects, you would need to exceed at least ten times that level.

And, even then, the effects include lesions on the teeth and the possible calcification of ligaments — not something you would necessarily want to have happen, but certainly not mind control. In 2015, the Cochrane Collaboration reviewed every study it could find on the benefits of fluoridated water, and concluded it may not offer its touted preventative benefits. However, the debate about the efficacy of flouridated water is a far cry from a government mind-control project.

Microwaves

(Credit: Kostenko Maxim/Shutterstock)

Kostenko Maxim/Shutterstock

They breathe life into day-old pizzas and cold casseroles, but do microwaves leech all the vital nutrients from our favorite foods?

Microwaves work by interacting with very specific molecules in food, most importantly water molecules, but fats and sugars as well. This is why your soup gets burning hot, but the plastic lid on your tupperware container doesn’t. The waves cause the molecules to vibrate, generating heat. Microwaves aren’t strong enough to actually break chemical bonds, however, meaning that they won’t destroy the nutrients inside your meals.

Some of the evidence for this claim comes from research showing that heating up some foods — especially by boiling them in water — serves to break down helpful compounds, such as antioxidants. However, cooking foods with different methods, such as by steaming, frying, baking or microwaving them, does not have the same effect.

A study dating all the way back to 1982 confirms as much, stating: “…no significant nutritional differences exist between foods prepared by conventional and microwave methods.” And according to CSIRO, Australia’s national agency, “if correctly used, microwave ovens offer a convenient and safe method of food preparation without any detrimental effects on consumer safety or nutrition.”

Bigfoot

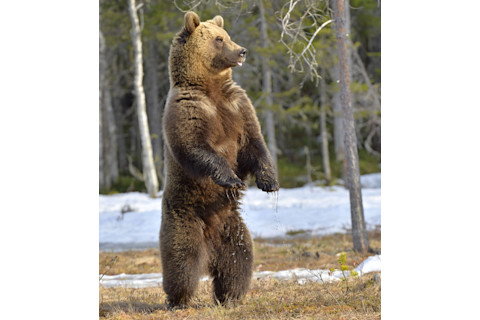

A brown bear standing on its hind legs. (Credit: Sergey Uryadnikov/Shutterstock)

Sergey Uryadnikov/Shutterstock

Mysterious creatures never fail to stir our imaginations, and it’s no surprise that cultures from across the globe tell tales of morphologically ambiguous hairy creatures roaming the backwoods. From the Yeti in the Himalayas to the Almasty in Central Asia and the Bigfoot that haunts our North American forests, wookie-like humanoids populate our collective imaginations.

Bigfoot has inspired amateur documentarians and fame-hungry hunters for decades now (it’s even the star of a show on Animal Planet), egged on by a wealth of supposed footprints, grainy photographs and first-person accounts dating all the way back to the Native Americans.

In 2014, a team of researchers led by Oxford University geneticist Brian Sykes conducted a DNA analysis of 30 hair samples less than a century old that purportedly came from sasquatches or similar creatures. Every sample was ultimately matched to known mammals, including cows, dogs and bears. While there was some controversy over their claim that several samples came from an extinct species of polar bear, their study found absolutely no evidence for a previously unknown species of hominid lurking in the wilderness.

Photographic and video evidence, most notably the Patterson-Gimlin film, have been subjected to intense scrutiny, but none have ever presented sufficient evidence to prove that Bigfoot exists or ever did exist. Bears seem to be a common culprit in Bigfoot cases. Bear footprints look somewhat similar to ours, and because they also occasionally stand on their hind legs like a human.

Steel Beams

(Credit: purgatoryironworks/YouTube)

purgatoryironworks/YouTube

The attacks on the twin towers on 9/11 stand as one of the most shocking moments in U.S. history, and for some the attacks seemed too coordinated to have come from a terrorist group. Instead, so-called “truthers” pin the blame on a government conspiracy.

One of the most-cited and well-publicized pieces of evidence offered by this group is the claim that jet fuel does not burn at high enough temperatures to melt the steel beams. By this logic, explosives or some other form of fuel must have been used to bring the buildings down.

While jet fuel, which burns at around 800 to 1,500 degrees Fahrenheit, may not reach the 2,750-degree melting point of steel, it is only about half as strong at 1,100 degrees, according to a comprehensive report compiled by Popular Mechanics in 2005. For the towers to collapse, the steel would not have needed to turn into a puddle of molten metal, it would only have had to bend enough to compromise the structural integrity of the building.

And, if you don’t believe us, perhaps this irate metalworker can convince you: