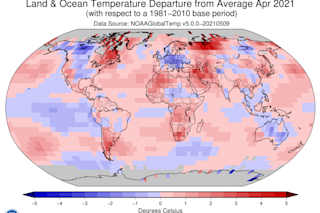

If you happen to live in North America's mid-section, or perhaps in central Europe or the land Down Under, it may come as no surprise that this past month was kind of chill compared to Aprils of recent years.

Mind you, none of Earth's land or ocean areas had a record-cold April, but as the map above shows, significant portions of the globe were cooler than average. Even so, other parts of the world were unusually warm — for example, a large part of Siberia, which already is experiencing wildfires that may portend yet another ferocious burning season.

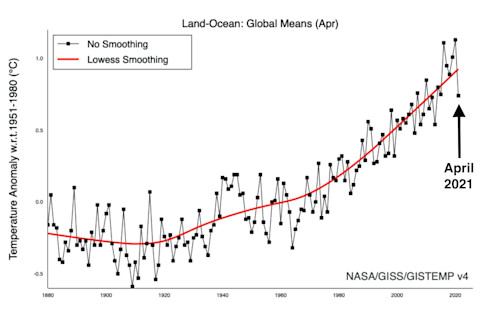

How did it all pan out on average globally? According to separate analyses released yesterday by NOAA and NASA, it was the coolest April since 2013. By NOAA's reckoning, eight other Aprils have been warmer in records dating back to 1880. (By NASA's independent analysis, nine other Aprils were.) Looking ahead, 2021 is likely to turn out much cooler globally than last year, which was the second warmest year on record.

"The 12-month running mean temperature is dropping fast...and probably will not reach a minimum until November this year," write Columbia University climate scientists James Hansen and Makiko Sato in a monthly climate update report. "That minimum is likely to be well below the 1970-2015 trend line...and 2021 will be much cooler than 2020."

Last month was much cooler than Aprils of the past few years. (Credit: NASA GISS with annotation by Tom Yulsman)

NASA GISS with annotation by Tom Yulsman

If things do pan out that way, would it mean that an acceleration of global warming they say has been occurring in recent years was actually just an anomaly?

"No, almost surely not," they write.

The relative chill of global average temperature that we’re seeing now is thanks in large measure to the lingering cooling influence of the La Niña phenomenon, not some underlying, long-term shift in the trajectory of global warming.

How La Niña Casts a Chill

Why does La Niña tend to put a damper on global surface temperatures? The phenomenon is characterized by a vast swath of cool surface water stretching along the equator to the west of South America. It's so vast, in fact, that it tends to depress the overall global average surface temperature.

But La Niña's cooling influence doesn't mean that extra heat energy trapped in the climate system by greenhouse gases has somehow escaped into space, never to be seen again. Instead, during a La Niña some heat energy from the atmosphere gets shifted into the deeper layers of the ocean. When La Niña's opposite, El Niño, kicks in, some of that heat will come to the surface and wind up back in the atmosphere, helping to warm the global average temperature.

This shifting of heat to and from the ocean means that in any given decade, the very warmest years are usually El Niño ones, and the coolest are usually La Niña ones, according to NOAA.

If you follow weather and climate news closely, you may know that NOAA yesterday declared La Niña dead. But that doesn't mean it's cooling impact has vanished. Surface waters of the equatorial Pacific are still quite cool. And according to Hansen and Sato, the overall influence of La Niña should linger for about five months.

But the impacts of El Niño and La Niña are ultimately short-lived blips imposed on the long-term trend line of global warming. As Hansen and Sato point out, the climate system is still dramatically out of energy balance — and at a record level, they say — thanks to the greenhouse gases we’re continuing to pump into the atmosphere. When the impacts of the current La Niña finally dissipate, that will still be true.

COVID and CO2

There was a significant drop in greenhouse gas emissions last year, in part because the COVID pandemic depressed economic activity, and also because of a continuing shift to renewable energy.

But the atmosphere — and thus the climate — haven’t really noticed.

The actual concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere continue to rise rapidly. In particular, the growth in atmospheric levels of methane – an extremely potent greenhouse gas — “is shocking,” according to Hansen and Sato. After stabilizing earlier in the 2000s, the growth has accelerated to its highest rate on record, at least in part because of fracking.

"There is a wide gap between reality and the picture that governments paint about the status of actions to limit global warming," they argue. "Actual government policies consist of little more than tinkering with domestic energy sources, plus goals and wishful thinking in international discussions."

Strong words. For more, and in particular a summary of the steps they say are necessary to avoid the worst climate impacts, check out their report. Here's the link again: http://www.columbia.edu/~mhs119/Temperature/Emails/April2021.pdf