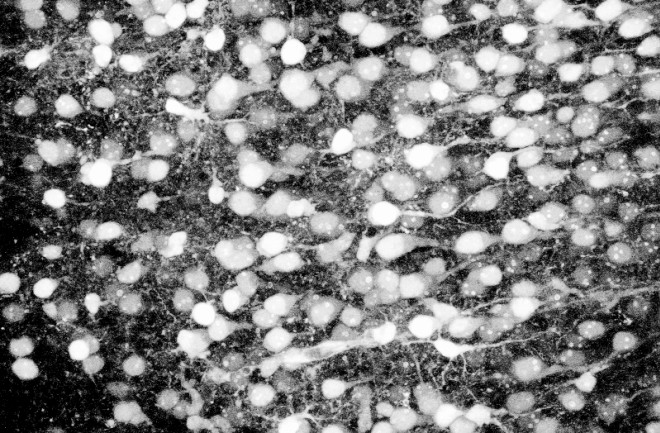

Calcium imaging techniques record the firing of individual mouse neurons and their pulses of electricity. (Credit: Yuste Laboratory/Columbia University) In 1949 psychologist Donald Hebb built a theory for how neurons in the brain behave during the learning process — basically, neurons that fire together wire together. Hebbs theorized that stimulating a group of neurons together causes these cells to then stick together and form a group — a neuronal ensemble. Repeatedly activating the ensemble, he believed, strengthened the connections between them, allowing them to all fire more efficiently. Today, Hebbian theory underlies biological explanations for learning, memory formation and brain plasticity. And now neuroscientists from Columbia University artificially generated one of these neuronal networks in mice cortices, and it may be one of the clearest demonstrations of the 67-year-old theory.

How the Brain Makes Memories

To create a neuronal network in mice, study coauthor Luis Carrillo-Reid stimulated a group of neurons in a mouse’s visual cortex with a precise, two-photon laser. The light excited neurons, which had been genetically modified to react to light, and caused them to fire. In 1982, neuroscientist John Hopfield, building on Hebbs' theory, proposed that stimulating just one neuron would simultaneously trigger an entire ensemble. When Carrillo-Reid activated a single neuron from the ensemble, its activity triggered the rest to fire. The artificial networks seemed to do exactly what Hebb and Hopfield predicted. “What we find is exactly what these two guys proposed, that if you fire a bunch of neurons together, they stick together, and if you trigger one neuron, you trip the entire ensemble,” says Rafael Yuste coauthor of the team’s paper published Thursday in Science. Yuste likens that process to the literary example of a character in Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, for whom the taste of a familiar cake triggers a cascade of related childhood memories. “The beginning of a memory can trigger an entire recollection of things,” he said. It’s the first time researchers have observed, in high resolution, pattern completion and what happens to individual neurons in an ensemble.

Connecting Neurons and Behavior

Carrillo-Reid and Yuste are both careful to point out that it isn't entirely clear if they artificially imprinted an actual memory in the mouse’s brain, or that forming these ensembles is definitely how the brain learns — it's all still theory. “There's still a bridge between these results that we're publishing and a demonstration that that's how learning works in humans,” says Yuste. “As much as our results are very exciting, we have not demonstrated that this is how learning works.” Their next step is to see if their artificial neuronal ensembles alter behavior in mice. Proceeding with Caution Despite several years of excitement about the potential of using optogenetics in the human brain, neuroscience is at least a decade away from creating or changing neural ensembles to treat patients with neurological disorders. The principle is sound enough, especially for disorders caused by misfiring neurons, from epilepsy to schizophrenia. “Now that we can go into the brain and burn in a pattern, it immediately raises the possibility of changing the patterns of firing, of activity in the neurons of these patients, to correct them,” says Yuste. “Myself, trained as an MD, I'm very interested in using this in patients to cure these mental diseases which are, at this point, untouchable.” Before that’s possible, neuroscientists will need a much more detailed understanding of the brain’s neural circuitry. Carrillo-Reid says he is currently involved in studies aimed at identifying abnormal activity patterns in specific ensembles associated with neurological diseases. Researchers also still need to develop ways to program and manipulate larger and more complicated neural ensembles. Scientists still don't know if optogenetics is even safe for humans, and there are a host of ethical issues to consider, given that these methods could potentially alter patients’ moods or behaviors. Those issues will be part of the agenda for a neuroethics symposium at Columbia University next month. “Yes, we're scientists, but we're also responsible citizens, and we want to make sure that we explore the difficult consequences of these methods before people get to the point where they're applying it to humans,” says Yuste.