The record-shattering heat wave currently scorching a vast swath of the western United States would have been considered extreme even if it had happened in the hottest part of the summer.

But summer is only just starting, making this heat wave particularly extraordinary.

Some 40 million Americans have already experienced triple-digit temperatures this week. Salt Lake City, Casper, Wyo. and Billings, Mont., set all-time record high temperatures on Tuesday (June 15th), with temperatures soaring to 107, 101 and 108 degrees, respectively. And yesterday, Las Vegas reached 116 degrees. That's two degrees higher than the previous record for the date, and just one degree shy of the highest temperature ever recorded in the city.

Thursday morning brought no relief. "It's a balmy 92 degrees to start the day in #Vegas," wrote the local National Weather Service office on Twitter. "Intense heat continues through Sunday!"

“What we are seeing in the Western U.S. this week — I’d be comfortable calling it a mega-heat wave because it is breaking 100-plus-year records, and it is affecting a wide region,” said Mojtaba Sadegh, a Boise State University climate expert, quoted in a Washington Post story.

Ring of Fire Weather

The West has been baking and drying in an extreme heat wave because it has been sitting for days under a sprawlig area of high atmospheric pressure. It's a phenomenon known as a "heat dome" in which the atmospheric circulation acts like a cap, trapping heat underneath.

The looping animation above vividly shows the large-scale, clockwise circulation pattern around the periphery of the heat dome, centered over the Four Corners region. The images in the animation were acquired by the GOES-17 satellite on June 16th. As the day progresses, watch as the air circulation entrains wildfire smoke smoke and then causes clouds to bubble up in a ring.

There has been and more of that smoke in recent days as the widespread heat has raised the risks of large wildfires. In fact, just yesterday, five new ones were reported in the West.

All told, 31 fires fires are blazing in eight western states plus Alaska. So far, they've scorched 413,966 acres, according to the National Interagency Fire Center. That's an area more than twice the size of the City of New York.

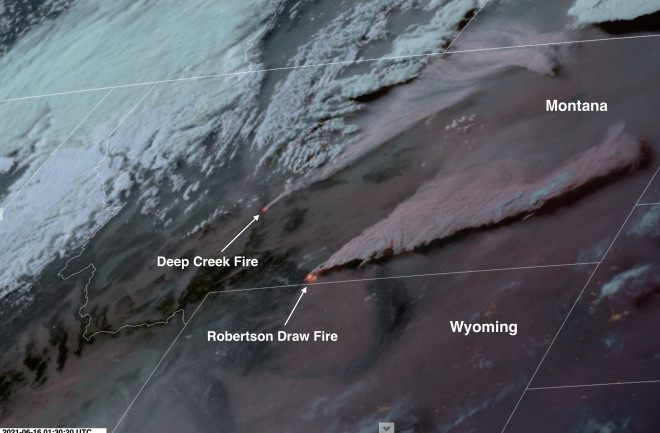

The satellite image at the top of this piece shows two of those fires exploding in intensity in Montana on Tuesday of this week. And this looping animation shows the evolution of those fires under hot, dry and windy conditions:

The animation consists of images acquired by the GOES-16 satellite. The Robertson Draw Fire is lower in the frame, and it produces a bigger smoke plume, which passes over Billings. The satellite imagery includes infrared data revealing the heat generated by flames. As of the morning of June 17, the blaze had scorched 24,273 acres south of the town of Red Lodge, and just to the north of the Wyoming border.

Orbiting 22,240 miles away in space, GOES satellites have captured other dramatic views of Western wildfires as well.

Utah's Pack Creek Fire, as seen here by GOES-16 on June 11, 2021, began with an unattended campfire about 10 miles southeast of Moab on June 9. By the morning of the 11th it had expanded to 5,000 acres. As of Thursday of this week, it had blazed through an additional 3,500 acres.

This next animation, consisting of false-color GOES-17 images, shows Arizona's Telegraph Fire. For me, the proximity of Phoenix — a metropolitan area of nearly 5 million people — emphasizes the human impact of this brutally hot, burning season.

The video begins in the early morning hours of June 15, 2021. The glowing orange infrared signature of the blaze is visible at the beginning, as are the lights of Phoenix, about 50 miles to the west, and Tuscon to the south and east. As the sun rises, smoke from the wildfire becomes visible.

Under hot conditions, the Telegraph Fire grew from an already large 91,227 acres on June 13th to 165,740 acres four days later — that's half the size of the City of Phoenix. This makes it the biggest wildfire in the West right now.

At times during this period, there was "some pretty extreme fire behavior with the fire weather conditions in the area," said Chad Rice, Planning Operations Section Chief, in a recent briefing. At one point, "the crews in there had a very dynamic situation, going into structures protecting them and getting chased out."

Brutal Drought

The Western wildfires have been fueled by vegetation that has dried out amidst a widespread drought that was already brutal even before the current heat wave settled in.

More than 58 million people live in areas suffering from some degree of drought in the West, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor. Extreme drought currently grips nearly 82 percent of the the region. (Note that Colorado and Wyoming are not included in these statistics.)

Perhaps most significantly, 26 percent of the region is in what's categorized as "exceptional" drought — this is the very worst category in the Drought Monitor's rankings. In records that date back two decades, that wide an extent of exceptional drought has never been seen before, until now. And it's not even close.

Climate Change Connections

Research reveals a clear connection between a warming climate and heat waves.

For example, climate change has already caused rare heat waves to be 3 to 5 degrees warmer on average over most of the United States. Already, extreme heat is one of the leading causes of weather-related deaths in the United States. Only hurricanes kill more people. If emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases continue at a high rate, we can expect another 3 to 5 degrees — and yet more deaths — to be added on top of that.

Research is also clarifying the connection between heat waves and dryness — and that connection seems to be getting stronger over time. In a study published in the journal Science Advances, Boise State's Mojtaba Sadegh and colleagues have shown that "compound dry and hot extremes" have increased substantially, "with an alarming increase in very rare dry-hot extremes. The area affected by concurrent extremes of heat and drought has also increased significantly."

In keeping with other recent work, the study also found that the main driver of dry-hot extremes has changed over time. In the 1930s it was meteorological drought, which occurs when dry weather patterns dominate an area. No longer. Warming temperatures have become the dominant driver in recent decades, according to Sadegh and his colleagues.

And just today, the connections between heat and drought became even clearer thanks to publication of a study in Nature Climate Change. Led by UCLA climate scientist Karen McKinnon, the study found that on the hottest summer days, humidity across the southwestern United States has dropped an average of 22 percent since 1950.

In California and Nevada, the decrease has been 33 percent. And in some areas, including parts of California's Central Valley, humidity on these hotest of days has plummeted by a staggering two thirds.

“In some cases we can’t dry out much more,” McKinnon said, quoted in a UCLA news release. (In the interest of full disclosure, McKinnon is the daughter of a good friend of mine.)

Hot temperatures are bad enough, because they raise the risk of wildfires. But lower humidity in the atmosphere can make things even worse. The explanation is actually a bit complex. But the long and short of it is that a drier atmosphere in a warming world becomes thirstier, sucking more and more moisture from soils and vegetation. And that, of course, drives the wildfire risk even higher.

Fire in the Forecast

The weather pattern currently bringing misery to so many people will begin to change, from east to west, starting tomorrow. But in some areas, the shift could bring thunder and lightning, which could ignite yet more wildfires. And winds from the storminess could fan the flames.

The Salt Lake City office of the National Weather Service isn't pulling punches about the risk, saying in its forecast discussion that "a significant severe fire weather event is expected Friday into Sunday." With that in mind, red flag warnings are now in place across most of the state through the weekend.

Starting Sunday and into Monday, temperatures will begin to moderate a bit in Arizona, Nevada and California. But they will still be higher than normal.

For the West as a whole, higher than normal temperatures are likely to persist, to one degree or another, all summer.